Reasons Not to Try to Turn a Baby

- Research article

- Open up Access

- Published:

This babe is not for turning: Women's experiences of attempted external cephalic version

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth book 16, Article number:248 (2016) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

Existing studies regarding women's experiences surrounding an External Cephalic Version (ECV) report on women who have a persistent breech post ECV and give birth by caesarean section, or on women who had successful ECVs and program for a vaginal birth. In that location is a paucity of understanding about the experience of women who attempt an ECV and so programme a vaginal breech nascence when their babe remains breech. The aim of this study was to examine women's experience of an ECV which resulted in a persistent breech presentation.

Methods

A qualitative descriptive exploratory pattern was undertaken. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted and analysed thematically.

Results

Twenty 2 (due north = 22) women who attempted an ECV and subsequently planned a vaginal breech birth participated. Twelve women had a vaginal breech birth (55 %) and 10 (45 %) gave birth by caesarean section. In relation to the ECV, there were five master themes identified: 'seeking an alternative', 'needing information', 'recounting the ECV experience', 'reacting to the unsuccessful ECV' and, 'reflecting on the value of an ECV'.

Conclusions

ECV should form part of a range of options provided to women, rather than a default procedure for management of the term breech. For motivated women who fit the safe criteria for vaginal breech birth, not being subjected to a painful feel (ECV) may be optimal. Women should be supported to access services that support vaginal breech birth if this is their choice, and continuity of care should be standard practise.

Background

The optimal way of birth for women who take a baby in the breech position at term is controversial. Since the Term Breech Trial [1], the availability of planned vaginal breech birth has diminished [2]. In Australia, in 2012, 87 % babies in the breech position were born by caesarean department (CS) [3]. In an effort to reduce the need for CS for breech, external cephalic version (ECV) has go a popular, safety practice and is recommended for women who have a straightforward pregnancy with a breech presentation near term [4–8]. The procedure is offered to women from around 36 weeks gestation with success at early on or late gestation being equivocal [9]. Success rates for ECVs are reported between 40 and threescore % [10]. As such, an ECV has been identified equally a potential mode to reduce CS rates [11] although consideration of the subsequent care for women whose babies remain breech is important.

At that place are few studies about a adult female's experience surrounding an ECV and her subsequent preference for mode of nativity [12–14]. These report on the experiences of women who have a persistent breech post ECV and then gave birth past CS, or on women who had successful ECVs that resulted in plans for a vaginal birth. In that location is a paucity of understanding about the experience of women who attempt an ECV then cull to plan a vaginal breech nascency when their baby remains breech. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine women'southward experience of an ECV that resulted in a persistent breech presentation. This is function of a wider program of research exploring the experiences of women who choose a vaginal breech birth and the midwives and doctors who cared for them [xv–17].

Methods

A qualitative descriptive study was undertaken [eighteen, 19]. This arroyo was selected to enable an bookkeeping of events from the participants of the study in order to better empathise their experiences. The participants were the women who had experienced an ECV and while their stories are described and explored, the findings seek to interpret meanings and actions from those stories.

This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee-Northern sector, South Eastern Sydney Local Health District, New S Wales Health. Reference: HREC 12/072 (HREC/12/POWH/163). Recruitment took place betwixt March and October 2013 from two hospitals in New Southward Wales that supported planned vaginal breech birth.

English-speaking women, who after an unsuccessful ECV planned a vaginal breech nascency for a singleton pregnancy in the past vii years regardless of their eventual mode of birth, were recruited in 2013. Women were identified from two Australian public maternity units in urban/metropolitan areas that supported women to accept a vaginal breech birth. A review of the hospitals' database that recorded women who planned a vaginal breech nativity was undertaken to identify eligible women. In full, 32 women were invited to participate with 22 (69 % response charge per unit) willing to exist interviewed.

Ii members of the research team conducted all the interviews. These took identify in women'due south homes as that was identified as the most convenient. Appointments were made with women at a time near suitable to them and normally family members or partners cared for the children while the interview took place. A series of open-ended questions were asked during interview, which lasted around 60 min. Each were recorded with a digital vocalization recorder and transcribed by a professional transcription service. Data collection ended when no new information arose from the interviews and it was agreed by the research team that data saturation had been achieved.

We used a similar process to that reported in our previous paper [15]. An inductive thematic analysis was used to place, depict, and analyse themes and patterns within the data [20]. The procedure meant that transcriptions were initially read and re-read past iii members of the research team and codes were identified. The codes were so examined for patterns and the underlying meaning of the issues identified were analysed within and between transcripts. The codes were refined and and then grouped according to commonalities which gave themes. These were shared with the research grouping once more and and then cantankerous-reviewed with the data, carefully because counterexamples or negative cases to ensure that the similarity and diversity of experiences were identified [21].

The themes are illustrated with quotes from the information. At the end of each quote is a code indicating the interview number and whether they had a caesarean section (CS) or a vaginal birth (VB).

Results

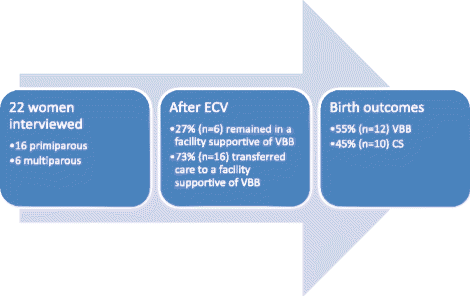

Twenty-2 women were interviewed, of which iii quarters were primiparous (n = 16; 73 %). All were Caucasian, and the bulk were educated to 3rd level. Well-nigh women were interviewed in the 3 years since their breech nascence. At the time of the ECV, almost (n = 16; 73 %) women were attending a hospital that did not support vaginal breech birth. Later on the breech presentation persisted, these women were informed that they would demand a CS and all decided to actively seek dissimilar carers to facilitate vaginal breech birth. The other vi (27 %) women were receiving care at a infirmary that supported vaginal breech nativity and continued with this intendance. Overall outcomes of birth were that twelve (55 %) women achieved a vaginal breech birth and 10 (45 %) gave birth by CS after labour had commenced (see Fig. 1).

Participants outcomes

V primary themes were identified. These were 'seeking an alternative', 'needing information', 'recounting the ECV experience', 'reacting to the unsuccessful ECV' and, 'reflecting on the value of an ECV'.

Seeking an alternative

Most women sought out other means to plow the babe and viewed the ECV as their last resort. Most tried more than one alternative therapy prior to attempting an ECV, some of which consisted of acupuncture, chiropractic, hypnotherapy, moxibustion, maternal positioning and yoga. This was motivated by the desire to avoid a medical procedure (ECV) and ultimately to avoid a CS birth. One adult female said:

"And so I thought the whole breeching thing - I'll fix that easy. It's not a problem. I merely practice acupuncture, I do chiropractic, I practice my exercises, he's going to plow'. That was my attitude. And I thought he was going to turn all the way up to, the D-Twenty-four hour period merely…yes. That didn't happen." CS3

Needing data

Women needed detailed individualised information to assist their controlling to take an ECV. The fashion information was presented by clinicians made a difference to the way women felt well-nigh attempting an ECV. For example:

"When he offered the pick he did it in such a way that information technology was and so welcoming, it didn't feel like it was a process and he bodacious me it would be up to the betoken that he felt the most pressure that he felt would exist safety for the baby. So that was a different way in which the ECV was painted and then I agreed to exercise the ECV." CS15

Despite this positive comment, many other women believed they were given insufficient information past their clinicians nearly the risks and benefits of an ECV. One woman expressed this by saying:

"I felt that I wasn't adequately educated as to what information technology was going to be like. I think I would have preferred a more consummate understanding of the process before I made the choice more than merely being told 'it'due south not pleasant'." VB10

Many women sought additional information from the cyberspace, social media and their friends and family regarding ECV. Data on the cyberspace was mostly reported every bit negative. This clouded the perception of the value of attempting an ECV. One adult female said:

"I stupidly Googled it before I went and I discover that people just want to share their stories when they are horrific." VB11

Some women felt they were not given a choice to opt out of an ECV, only that it was an expected step in the course of management for a breech baby. I woman expressed this lack of choice saying:

"I don't recollect it was actually presented equally an option it was just presented equally the next step." VB17

Recounting the ECV experience

When asked how they felt well-nigh the experience of having the ECV performed, the majority of women responded that the procedure acquired them physical pain. Because of the subjective nature of the feel of pain, some of the women compared it to other painful events in their life, like childbirth. For example:

"I can exercise pain. I didn't have drugs for my kickoff labour and I didn't have drugs for my second labour.. but that was, incredibly painful." VB1

Some women continued to have pain for some time afterwards the procedure. One woman said:

"I call up going to bed afterwards and trying to sleep 'crusade I was just in so much pain. And it really felt like someone had pummelled me, I had been through an absolute wringer." VB22

Reacting to an unsuccessful ECV

The reaction to a persistently breech baby was mixed. Nigh women had a strong emotional response, simply reactions varied dependent upon where the ECV was attempted. For women who were already in a hospital supportive of vaginal breech birth, the significance of an unsuccessful ECV was negligible equally the option of vaginal nascence was already in place prior to the procedure. For the women who were not given this option, thwarting and distress were reported. The availability of vaginal breech birth for these women was crucial to how they felt most the consequence of the ECV. These women expressed feelings of disappointment, devastation and unacceptance of the consequence of having a baby remaining in the breech position. For example:

"I definitely didn't accept it. And I remember when I came home from the ECV that had failed and I was, you lot know, again, wailing and crying. Just admittedly devastated." VB17

Women, cared for in hospitals that did not support vaginal breech nascence, hinged their hopes on a successful ECV as they felt it was the last resort to be able to continue along their path of planning a vaginal birth. One women woman said:

"It was atrocious. I was quite traumatised after that [ECV]. I call up also knowing that this was my terminal chance, if he didn't turn that I would accept to have a caesarean." VB14

In comparison, women who were enlightened of the option of vaginal breech birth prior to ECV were not as concerned when the procedure did non turn the infant. For instance:

"Nosotros walked away from that and I recollect at that betoken I began to accept that she wasn't going to turn dorsum. And that I was going to be delivering her breech [vaginally]." CS5

Reflecting on the value of ECV

Virtually half of the women (46 %) said they would not endeavor an ECV in a future pregnancy. Reasons for this were three-fold. Firstly, the experience caused physical hurting. This was expressed past i adult female as:

"So they're pushing your tum effectually and it's just bloody excruciating… it just didn't feel good… Never, never, never, again will I ever, ever, do that, never." VB10

Secondly, ECV was seen equally a procedure that introduced excessive risk to the baby that the women considered unnecessary, and some felt guilty for this. For case:

"felt really guilty that I'd possibly brought a trivial chip of distress to my babe in utero.. would never attempt an ECV if I was breech 2d fourth dimension effectually." VB2

Thirdly, the option and availability of a planned vaginal breech birth meant the women who were already in a hospital supportive of vaginal birth did not capeesh that an ECV to promote cephalic presentation was worthwhile because the fetal presentation was inconsequential for their pregnancy and birth. Many women who sought out the selection of vaginal breech birth commented that if the pick of vaginal breech birth had have been presented and available prior to attempting an ECV then they may not have chosen to attempt it. Ane adult female said:

"I think I wish I'd had more information almost the ECV and that information technology's non necessarily something that you need to do.. and so from what I know now, I wouldn't necessarily brand that choice." VB8

Discussion

This study describes Australian women's experiences who underwent an ECV which resulted in a baby who remained a breech presentation. Other studies have described women'southward experiences of having a breech presenting baby [22–24] and ECV [13, 14, 25–27]. Our findings add together to the understanding of women'due south experiences with a breech-presenting baby in the late 3rd trimester of pregnancy as many women are offered an ECV,

It was mutual for women to seek out a variety of complementary therapies for the relief of pregnancy-related complaints and symptoms [28], and this included turning babies [23]. This study showed that women used alternative therapies to endeavor spontaneous cephalic version. Even so, few were reported in the literature as having any major effect on turning babies, although moxibustion (a Chinese herbal medical intervention that stimulates acupuncture points) may have some effect in reducing CS rates when used in conjunction with positional therapies [29, 30].

Alternative therapies can likewise be used to reduce the discomfort of an ECV. Women were non given analgesia during the ECV in this report, although methods to reduce discomfort can include hypnosis [31], inhalation analgesia, [32], injectable analgesia, and regional amazement [33]. Nonetheless, pain levels vary in women and women's perception and recollection of pain are important. Vlemmix et al. [25] ended that a woman's willingness to hold to undergo an ECV is influenced past her perception of the pain and the likely success of converting her baby to a cephalic presentation. Women's recollection of pain tin can also be diminished if their ECV was successful [26]. This may explain why the majority of women in this study reported it as a painful experience, as they all had an unsuccessful ECV, although this retention may have been compounded by the distress three quarters of them felt when they were told to expect a CS.

The way information and options for nativity were presented was important. The timing, style and content of the information were fundamental to women's levels of feet. Discussions with health professionals surrounding myths (predominately found on the internet) and risks and benefits for ECV, vaginal breech birth and caesarean section were appreciated. In particular, risks and benefits are useful when articulated in a clear, easy to understand format especially the success rates. ECV success rates of twoscore–lx % have been reported [ten], however information technology is pertinent to reveal local rates to women likewise as talk over rates for women's private breech-positioned baby (eg. frank, footling). For instance, footling breech babies take ii.77-times more likelihood of remaining cephalic after ECV than babies in a frank breech position [34]. Data to assist controlling can as well be facilitated through a determination-making tool. For example, a small study in Canada using an sound-guided workbook for women with a breech presentation was found to be helpful, although self-rated feet levels were not lowered significantly after using the decision assist [35].

Breech positions have long been seen as 'malpositions' of the fetus. It could be argued that in that location is a identify for respecting women's pick to pass up ECV and endeavour for a vaginal breech nascence. Other countries, such as Finland, where i in three women with breech babies are eligible and willing to endeavor for a vaginal nascence have this mental attitude towards breech-positioned babies [36]. Furthermore, some other study by the same authors suggested that a trial of vaginal breech birth is as positive as a vertex birth experience for women [22]. Considering this, it may be time to motion away from the approach of women being told their babies are in the 'wrong' position, and that turning them to a cephalic presentation is the only desirable choice.

This study included a selective group of women because they were highly motivated to pursue a vaginal breech birth. This may not reflect the general population of women, many of whom consent to a caesarean section when their baby is persistently breech. Despite this, these women provide a unique opportunity to understand the experience of women who accept an ECV that does non plow their baby. Qualitative studies such every bit this provide a window into the experience for these women and could be reflective of other women'south experiences.

Conclusion

Understanding women'southward experiences is important for doctors and midwives who provide care for women with a infant in the breech presentation belatedly in pregnancy. ECV should grade function of a range of options provided to women, rather than a default process for direction of the term breech. For motivated women who fit the condom criteria for vaginal breech nativity, not existence subjected to a painful experience (ECV) is optimal. Given many women reported that they would non endeavour an ECV in a time to come pregnancy, access services that back up vaginal breech birth needs to be made available.

References

-

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean department versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375–83.

-

Daviss B-A, Johnson KC, Lalonde AB. Evolving testify since the term breech trial: Canadian response, European dissent, and potential solutions. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32(3):217–24.

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mothers and Babies Report, 2012. Canberra: AIHW; 2014.

-

The Purple Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Breech Presentation at Term. Melbourne: RANZCOG; 2013.

-

Regal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. External cephalic version and reducing the incidence of breech presentation Guideline no. 20a. London: RCOG; 2010.

-

Nassar North, Roberts CL, Barratt A, Bong JC, Olive EC, Peat B. Systematic review of agin outcomes of external cephalic version and persisting breech presentation at term. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol. 2006;20(ii):163–71.

-

Hutton EK, Hofmeyr G. External cephalic version for breech presentation before term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006 (Issue one. Art. No.: CD000084. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000084.pub2).

-

Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BWJ, van der Postal service JA. External Cephalic Version–Related Risks: A Meta-assay. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(five):1143–51.

-

Hutton EK, Hannah ME, Ross SJ, Delisle MF, Carson GD, Windrim R, et al. The Early on External Cephalic Version (ECV) 2 Trial: an international multicentre randomised controlled trial of timing of ECV for breech pregnancies. BJOG: IntJ Obstetr Gynaecol. 2011;118(five):564–77.

-

Hofmeyr G, Kulier R, West H. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (Event 4. Fine art. No.: CD000083. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3).

-

Cho L, Lau W, Lo T, Tang H, Leung Westward. Predictors of successful outcomes after external cephalic version in singleton term breech pregnancies: a nine-year historical cohort study. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;eighteen(1):xi–nine.

-

Menakaya UA, Trivedi A. Qualitative cess of women's experiences with ECV. Women Birth. 2013;26(1):e41–iv.

-

Rijnders M, Offerhaus P, van Dommelen P, Wiegers T, Buitendijk Due south. Prevalence, Outcome, and Women'southward Experiences of External Cephalic Version in a Low-Risk Population. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care. 2010;37(ii):124–33.

-

Say R, Thomson R, Robson S, Exley C. A qualitative interview study exploring pregnant women's and wellness professionals' attitudes to external cephalic version. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):i–9.

-

Homer CS, Watts NP, Petrovska K, Sjostedt CM, Bisits A. Women's experiences of planning a vaginal breech nascency in Commonwealth of australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;xv:89.

-

Catling C, Petrovska K, Watts N, Bisits A, Homer C. Barriers and facilitators for vaginal breech births in Australia: Clinician's experiences. Women Nascence. 2016;29:138–43.

-

Catling C, Petrovska M, Watts N, Bisits A, Homer C. Intendance during the decision-making phase for women who desire a vaginal breech nascence: Experiences from the field. Midwifery. 2016;34:111–6.

-

Sandelowski Thousand. Whatsoever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–forty.

-

Sandelowski Yard. What's in a name? Qualitative clarification revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84.

-

Liamputtong P. Qualitative Research Methods. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2005.

-

Taylor B, Kermode S, Roberts K. Enquiry in Nursing and Wellness Intendance: Evidence for Practise. 3rd ed. Nelson: Thomson Learning; 2006.

-

Toivonen E, Palomaki O, Huhtala H, Uotila J. Maternal experiences of vaginal breech delivery. Birth. 2014;41(4):316–22.

-

Guittier 1000-J, Bonnet J, Jarabo 1000, Boulvain M, Irion O, Hudelson P. Breech presentation and choice of mode of childbirth: A qualitative study of women's experiences. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):e208–13.

-

Glasø AH, Sandstad IM, Vanky E. Breech commitment—what influences on the mother's choice? Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2013;92(9):1057–62.

-

Vlemmix F, Kuitert G, Bais J, Opmeer B, van der Mail J, Mol BW, et al. Patient's willingness to opt for external cephalic version. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 2013;34(1):15–21.

-

Bogner Chiliad, Hammer BE, Schausberger C, Fischer T, Reisenberger K, Jacobs V. Patient satisfaction with childbirth later external cephalic version. Arch Gynecol Obstetr. 2014;289(3):523–31.

-

Truijens SEM, van der Zalm K, Popular VJM, Kuppens SMI. Determinants of pain perception afterwards external cephalic version in pregnant women. Midwifery. 2014;xxx(3):e102–vii.

-

Adams J, Sibbritt D, Lui CW. The use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: a longitudinal study of Australian women. Nativity. 2011;38(three):200–6.

-

Zhang Q-H, Yue J-H, Liu M, Sun Z-R, Sun Q, Han C, et al. Moxibustion for the correction of nonvertex presentation: a systematic review and meta-assay of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:241027.

-

Coyle G, Smith C, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 (Issue 2. Fine art. No.: CD003928. DOI: ten.1002/14651858.CD003928.pub2.).

-

Guittier M-J, Guillemin F, Brandao Farinelli E, Irion O, Boulvain M, de Tejada BM. Hypnosis for the Control of Hurting Associated with External Cephalic Version: A Comparative Report. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(10):820–5.

-

Burgos J, Cobos P, Osuna C, de Mar CM, Fernández-Llebrez 50, Astorquiza TM, et al. Nitrous oxide for analgesia in external cephalic version at term: prospective comparative study. J Perinatal Med. 2013;41(six):719–23.

-

Weiniger CF, Ginosar Y, Elchalal U, Sela HY, Weissman C, Ezra Y. Randomized controlled trial of external cephalic version in term multiparae with or without spinal analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104(5):613–8.

-

Burgos J, Melchor JC, Pijoán JI, Cobos P, Fernández-Llebrez L, Martínez-Astorquiza T. A prospective study of the factors associated with the success rate of external cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;112(one):48–51.

-

Nassar N, Roberts CL, Raynes-Greenow CH, Barratt A. Development and pilot-testing of a decision aid for women with a breech-presenting baby. Midwifery. 2007;23(1):38–47.

-

Toivonen E, Palomäki O, Huhtala H, Uotila J. Selective vaginal breech delivery at term—still an selection. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2012;91(10):1177–83.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would similar to acknowledge the women who freely gave their time to be interviewed for this study

Funding

The study was supported by a small scholarship grant from the Australian Higher of Midwives, New Due south Wales Co-operative.

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be shared. This is considering there is identifying data within the files.

Authors' contributions

The contribution to authorship is: CC contributed to writing and editing, NW interviewed the women, analysed the data and contributed to the writing, KP interviewed the women and, AB contributed to the conception, design and protocol, CH coordinated the report, contributed to the protocol, design and writing, and canonical the concluding draft. All were involved in revision and last approval.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Ideals approval and consent to participate

This written report received approving from the Human Inquiry Ethics Committee-Northern sector, South Eastern Sydney Local Health Commune, New South Wales Health. Reference: HREC 12/072 (HREC/12/POWH/163).

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and point if changes were fabricated. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watts, N.P., Petrovska, K., Bisits, A. et al. This baby is non for turning: Women's experiences of attempted external cephalic version. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 248 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1038-1

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1038-1

Keywords

- External cephalic version

- Breech presentation

- Pregnancy

- Qualitative research

- Caesarean section

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-016-1038-1

Post a Comment for "Reasons Not to Try to Turn a Baby"